|

Article Page 1

Article Page 2

Article Page 3

Article Page 4

Article Page 5

Bibliography

Cover Gallery 1

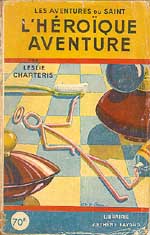

Cover Gallery 2

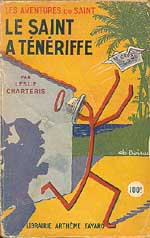

Cover Gallery 3

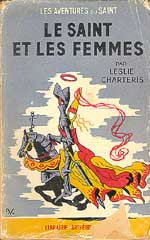

Cover Gallery 4

Cover Gallery 5

Cover Gallery 6

Cover Gallery 7

German covers by Regino Bernad

Le Saint Detective Magazine 1

Le Saint Detective Magazine 2

Le Saint Detective Magazine 3

Le Saint Detective Magazine 4

About Nero Wolfe & The Toff

About artist

Regino Bernad

The Saint on French Radio

French-English

Text Comparisons

De Saint (The Dutch Saint)

© 2001 Jean-Marc Lofficier. This article first appeared in a slightly different form in the Summer '94 issue

of The Epistle.

Thanks to Ian Dickerson for Research Assist.

Thanks to Dan Bodenheimer, Marcel Bernadac, and Patrick Verdant for additional cover scans.

|

The history of the French Saint books can pretty much be broken into five sections:

- (1) the "originals", i.e.: the translations and/or adaptations of Leslie

Charteris' work, which fill the first twenty-five slots in the series.

- (2) the radio "fix-ups" (a term coined by critic Peter Nicholls, meaning

a book composed of separate stories cemented together), derived from the Saint radio scripts, which occupy the next ten slots.

- (3) and (4) the "comic stories", books loosely adapted from the New York Herald-Tribune comic-strip which fill

almost the entirety of the rest of the series. (This period can itself be divided into two "sub-periods",

according to style and contents.)

- (5) a few, latter-day, Charteris' short-story collections, some uncollected stories,

and finally, the publication in the early 1980s of a number of Charteris "collaborations."

In order to make the article easier to read, I have bolded the original English titles when known. In the case of Charteris' own stories, which have

often been published under different titles in England in in the United States, I have chosen what I hope to be

the most recognizable title, I have italicized my translations of the French titles for the pastiches.

1. The "originals"

(1938-1949) 1. The "originals"

(1938-1949)

The Fayard Saint series debuted

with The Saint in New York (No.

1) which, as every devotee knows, opens with a memo sent by Teal to Fernack recapping some of Simon Templar's more

notorious adventures, including Meet the Tiger!,

The Last Hero and Knight Templar. Why therefore begin a series with

material which was bound to confuse a new reader?

Further confusion must have ensued when one realizes that the second volume released by Fayard was Knight Templar (translated under the title of

The Heroic Adventure), a direct

sequel to The Last Hero.

The reason for this strange release pattern is that there were previous French Saint editions of The Last Hero

and Meet the Tiger!, published

in 1935 by Editions Gallimard in their "Detective" imprint. Fayard, therefore, did not have the rights

to publish these books -- yet -- but legitimately assumed that the reader of the times could refer to them if they

wished to do so.

The copyright

on The Saint in New York is 1938.

Normally, the French copyright is supposed to indicate the date of the first French publication of a work (i.e.:

referring to a specific translation). However, mistakes creep up frequently. Sometimes, the later date of printing

of a subsequent edition is substituted. For example, the copyright on a subsequent edition of Knight

Templar is 1946, even though the first Fayard edition of that book was

released in 1938. The copyright on Thieves' Picnic

(No. 10) is mistakenly listed as 1930, even though that particular book was written by Leslie Charteris in 1937!

This is just to illustrate the fact that French copyright mentions are notoriously unreliable, thus making serious

research all but impossible. The copyright

on The Saint in New York is 1938.

Normally, the French copyright is supposed to indicate the date of the first French publication of a work (i.e.:

referring to a specific translation). However, mistakes creep up frequently. Sometimes, the later date of printing

of a subsequent edition is substituted. For example, the copyright on a subsequent edition of Knight

Templar is 1946, even though the first Fayard edition of that book was

released in 1938. The copyright on Thieves' Picnic

(No. 10) is mistakenly listed as 1930, even though that particular book was written by Leslie Charteris in 1937!

This is just to illustrate the fact that French copyright mentions are notoriously unreliable, thus making serious

research all but impossible.

Dedicated researchers might further note that the copyright on Thieves'

Picnic is in the name of "A. Fayard et Cie (& Co.)", while

all the other books in the series were copyrighted in the names of "F. Brouty, J. Fayard et Cie" until

1956 (No. 47), when suddenly the copyright became "Librairie Arthème Fayard", until the end of

the series. One can only assume that F. Brouty bought stock in the original Arthème Fayard publishing company

sometime around 1939, at which time the original Arthème Fayard was succeeded by J. Fayard. The later change

to Librairie Arthème Fayard must have been the result of some form of corporate restructuring.

Meet the Tiger! and The Last Hero were eventually re-released, first

by Gallimard again in 1951, then by Fayard in 1962, respectively as No. 70 and No. 72 in the series. However, the

copyright on these two books -- even in the Fayard edition -- remains Gallimard's, even though the books were translated

by the same writer. From this, it is clear that, even though Meet the Tiger! and The Last Hero

were first published in France in the 1930s, for some contractual reasons, the rights to these novels did not become

available to Fayard until the early 1960s.

1b. The Translators 1b. The Translators

The matter of the identity of the translator of the French Saint books remained for a long time relatively clouded

in mystery. Nos. 1 to 6, 9 to 14, 23 and 70 (Meet the Tiger!) were credited to "E. Michel-Tyl", with No. 19 being specifically credited to

"Ed. Michel-Tyl" -- "Ed." being for Edmond.

Edmond Michel-Tyl (1891-1949)

was the author of a number of adventure and romance novels, including Marquita

au Col d'Or [Marquita of the Golden

Neck] (Tallandier, 1936) and La

Vallée du Mystère [The

Valley of Mystery] (Librairie des Champs-Élysées, 1940);

he also translated many other crime novels, such as William Irish's The

Bride Wore Black, Rex Stout's Nero Wolfe, Rafael Sabatini's Sea Hawk and Captain

Blood, Dashiell Hammett's The

Maltese Falcon, and novels by R. K. Goldman, Hugh Austin, Sidney Fairway,

Erskine Caldwell, etc.

No. 8 (in a later edition) and Nos. 27 to 29 are credited "M.-E. Michel-Tyl" -- note the periods and

the hyphen. All this confusion in the credits merely reflects the fact that, after Edmond Michel-Tyl's death in

1949, his wife, Madeleine (who

had previously been collaborating with her husband), took over his duties.

Nos. 7 and 15 (in later editions), Nos. 22, 24 to 26, 30 to 69, 71, 72 (The

Last Hero, which is odd since, in in all logic, this book should have

been translated by Edmond and not by Madeleine), Nos. 73 to 78 are all credited to "M. Michel-Tyl" --

the credit normally given to Madeleine Michel-Tyl.

Clearly, mistakes were made in the attribution of credits in the reprinting of later editions, and it is likely

that Nos. 7, 8 and 15 -- at least -- are indeed the work of Edmond and not of Madeleine, who took over the series

somewhere in the mid-No.20s -- probably with No. 24, the first of that sequence to be credited to "M. Michel-Tyl"

instead of "E. Michel-Tyl".

Finally, a letter

from Jenny Bradley, Leslie Charteris' French agent, dated 27th February 1969, indicates that Madeleine Michel-Tyl

was somewhat extensively assisted by Fayard editor Francis Didelot, himself a well-known writer/editor of French

mystery novels. Mrs. Charteris remarked that Leslie Charteris himself stepped in when the quality of the French

novels had started to come down, and ended up working in "quite a close partnership" with Madeleine Michel-Tyl.

He offered the New York Herald-Tribune

comic strips as source material -- which contained much specific dialogue as well as descriptions -- thereby facilitating

the novelisation process. Finally, a letter

from Jenny Bradley, Leslie Charteris' French agent, dated 27th February 1969, indicates that Madeleine Michel-Tyl

was somewhat extensively assisted by Fayard editor Francis Didelot, himself a well-known writer/editor of French

mystery novels. Mrs. Charteris remarked that Leslie Charteris himself stepped in when the quality of the French

novels had started to come down, and ended up working in "quite a close partnership" with Madeleine Michel-Tyl.

He offered the New York Herald-Tribune

comic strips as source material -- which contained much specific dialogue as well as descriptions -- thereby facilitating

the novelisation process.

In any event, the Michel-Tyls are, without a doubt, the greatest of all of Leslie Charteris' "collaborators"

and, to the extent that they "rewrote" the original comic-strip stories, virtually co-authors. Edmond

Michel-Tyl, a talented writer in his own right, succeeded wonderfully in duplicating Charteris' light style and

wry characterization in French, perhaps inspired by, or following in the literary tracks of, Maurice Leblanc, creator of the incredibly popular character

of Arsène

Lupin, gentleman-burglar, which must have been one of Charteris' major

source of inspiration when creating the Saint.

1c. The "originals" -- continued (1938-1949) 1c. The "originals" -- continued (1938-1949)

After Knight Templar (No. 2) and

She was a Lady (No. 3), the Fayard

series continued with Saint Overboard

(No. 4), Alias the Saint (No.

5), Getaway (No. 6) and The Saint versus Scotland Yard (No. 7), the latter

bizarrely copyrighted in 1956 in a later edition printed in 1964, even though the first Fayard edition was released

in 1939, illustrating again the vagaries of French copyrights.

The next two volumes complicate the researcher's life. The first, released under the translated title of The Saint Here! (No. 8), in addition to being

also wrongly copyrighted to 1951 (even though it was originally released in 1940), contained only two stories,

The Gold Standard and The Death Penalty, taken from the original three-story

collection The Saint and Mr.Teal

(a.k.a. Once More the Saint).

The third story, The Man from St.Louis,

for reasons unknown, was published in The Companions of the Saint (No. 9), an equally incomplete translation of the original three-story collection Enter the Saint.

Having to make room for The Man from St.Louis

in The Companions of the Saint,

Fayard then chose to defer the publication of the first story of that book, The

Man Who Was Clever, to No. 18 of its own series. To further complicate

matters, The Man from St. Louis,

The Death Penalty and The Gold Standard were all released separately

in 1950, under different titles, by another French publisher, Editions Ferenczi, in their "Le Verrou" (The

Deadbolt) imprint.

As we have seen,

No. 10 was a straightforward adaptation of Thieves' Picnic (it only stands out because of its puzzling 1930 copyright), No. 11 of The Misfortunes of Mr.Teal and No. 12 of Follow the Saint. These three books were published

in 1941. As we have seen,

No. 10 was a straightforward adaptation of Thieves' Picnic (it only stands out because of its puzzling 1930 copyright), No. 11 of The Misfortunes of Mr.Teal and No. 12 of Follow the Saint. These three books were published

in 1941.

After an interruption due to the war, difficulties begin again with No.13, which was released in 1945. Again for

reasons unknown, Fayard chose to rearrange the order of the short stories published. No.13, whose French title

translates as The Saint Goes to War,

reprinted The Wonderful War from

Featuring the Saint, and The High Fence and The

Case of the Frightened Innkeeper from The

Saint Goes On. The third story of that volume, The

Elusive Ellshaw, was later used in No. 22. As for the other two stories

from Featuring the Saint (The Logical Adventure and The

Man Who Could Not Die), they were used in conjunction with The Man Who Was Clever (see above) to make up

No.18, entitled The Mark of the Saint.

The series continued with adaptations of The Saint on Guard (No.14) and The Saint Plays with Fire a.k.a. Prelude for War

(No. 15). This title may lead to some confusion as a latter volume (No. 37) bears a French title which also translates

as The Saint Plays with Fire,

while No.15's French title translates as The Saint Plays... And Wins.

The Ace of Knaves (No. 16) and

The Saint in Miami (No. 17) followed.

No. 18 was, in effect, an original collection by gathering the three stories listed above, under the title of The Mark of the Saint.

This was followed by an adaptation of The Saint Steps In (No. 19) and The Saint Goes West (No. 20). Perhaps for reasons of space, the latter only reprinted the Arizona and Hollywood

stories. Fayard eventually combined the third story, Palm Springs, with The Ellusive Ellshaw

to make yet one more "original" collection, under the title of The

Saint Leads the Dance (No. 22). In 1960, a French motion picture adapting

the Palm Springs short story was released under the same title.

The series went on, with adaptations of The Saint Sees It Through (No. 21) and Call for the Saint (No. 23), released in 1948. Fayard then discovered that they were running out of original

Saint stories, just as the popularity

of their books in France was growing by leaps and bounds.

First, they decided

to put out two more collections of short stories collections. No. 25 was a straightforward translation of Saint Errant. First, they decided

to put out two more collections of short stories collections. No. 25 was a straightforward translation of Saint Errant.

No. 24, on the other hand, was an original collection, entitled The Saint

Has Fun. In this book, Fayard picked and chose stories from The Brightest Buccaneer (two stories), The Saint Intervenes (five stories) and The Happy Highwayman (seven stories). This was

the first book sequentially credited to Madeleine Michel-Tyl, barring exceptions made for possibly erroneous credits

in earlier volumes.

The stories which were not included in The Saint Has Fun were later used in two more original collections, released as No. 69 (The Trumps of the Saint) and No. 76 (Again the Saint!). Why were these stories not

used earlier? I do not know.

The Noble Sportsman (from The Saint Intervenes) was translated and published

in Le Saint Detective Magazine No. 24, but not included in the books. The Uncritical

Publisher (also from The Saint

Intervenes) was not translated at all! The likely reason for these rather

bizarre omissions is either page count, or the editors simply forgot about them! All in all, a rather confusing

situation.

(Note: There is a 1945 French-Canadian

of The Saint Intervenes, Le Saint intervient, published by Editions Modernes

Ltée, translated by Madeleine Didayer, and it is likely that the "missing" stories were included

there.)

In any event, with less original material to translate, and a growing demand for more stories, the time had come

for Fayard to develop its own homegrown substitute.

PART 2 TO BE CONTINUED ON NEXT PAGE:

|