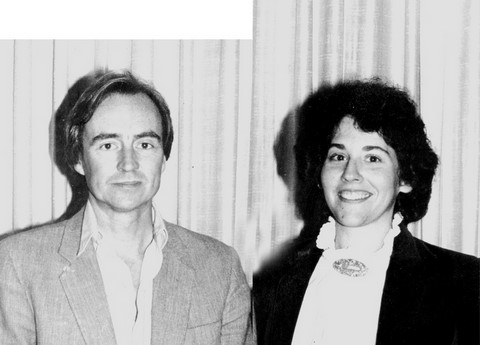

Wes Craven

Q: How did you get started in films?

Wes CRAVEN: I wasn't allowed to see movies when I was a child. It was against the religion I was raised in, Fundamentalist Baptist. I didn't go into a commercial movie house until I was a sewnior in college, and that was on the sly. It wasn't until I was in graduate school that I immersed myself in films. Then, I went to see all the films by Bergman, Fellini, etc.

The first film I made was when I was teaching. Some students came to me and said, "We see you have a camera, would you be our faculty advisor on a movie we want to make? You can shoot it." I said, "Sure", and got all of these free rolls of film from the drama department, and we went out and made a 45-minute MISSION IMPOSSIBLE spoof. We taught ourselves how to edit just by doing it. We didn't have any sort of editing machine, so we did it on a school projector. Splices were scotch-taped, and then glued for the final version. We couldn't figure out how to put sound with the movie. We knew that there was some film that had sound stripes along one side, but then we couldn't figure out how to do any sound overlap, or put music on there. So we did all our sound on a 1/4-inch tape, and then ran it at the same time with the projector, and we had a rheostat so we could slow it down a little bit or speed it up to keep it roughly at the same place.

We showed the picture at the local school auditorium. Well, we were smart enough to put everybody at the school, and everybody in the town that was of any significance, in the movie. So we had this huge turnout, and we made more than the cost of the movie in the first night! The next week-end, we showed it at the college that shared the town, and had another sell-out crowd. Then, we showed it at another college, that was fifteen miles down, and they all came to see it. So we made a lot of money. We had this great cast and crew party afterwards, and we spent it all on that!

From this, I got the bug. I wasn't happy teaching. I was enjoying the teaching, but not the grades. The students that would come and say, "I'm going to be drafted if you don't give me an A". The Department Chairman wanted me to get a PhD on Elizabethan Lutes in the Time of Chaucer, or something that obscure. So I quit my job, I went to New York, and I looked that summer for a job in film, but I wasn't able to find anything.

I went back to upstate New York, and I taught a year of High School at a terrible school. At the end of that summer, I was talking to a student friend of mine, and he said he had a brother who was a film editor. That was Harry Chapin, who had once won an Oscar for, I believe, the editing of LEGENDARY CHAMPIONS, a short film on the great champion boxers.

So, I sat down with Harry, and he was very kind. He was working on a Steinbeck. He showed me how a film was put together. I sat with him for about a week, just watching him cut. He explained to me why he was cutting, pacing, and a great deal of things which stuck with me to this day. At about the end of that week, a man whose offices we were renting the room in, fired his messenger and said, "If you know anyone who wants a job as a messenger, I'm looking for one." I was 30-year old, had a Master's Degree in Philosophy, two kids, and took the job as a messenger! That's how I got into film!

It was a film post-production house and, within ten months, I was Assistant Manager! Then, I quit that job for an assistant editing job. During that time, I crammed myself on film. I would work at night, synching up rushes or documentaries all over town, and got to know the young documentary film crowd in new York.

After that job, I drove a cab in New York for about three months, looking for a job in actually making a film. I finally got a chance on this small film that was being done by a 27-year old named Sean Cunningham. It was a small, homemade film, and I got the job of synching up rushes determined on the system editing, and it turned into a full-time editing job, and even some directing, because he was having a falling out with the film-maker that was working with him. We ended up finishing this film together.

The film came out, and made around $7 million. It had costed about $70,000. It was called TOGETHER, and very few people have heard of it, but it played all over the country for a summer. It was sort of like a sensitivity-training course for couples. It had a little nudity here and there. We all called it "Reader's Digest Sex". It was Marilyn Chambers' first film. She did a nude diving scene in it. But it had nothing beyond that. It talked about how to be more attuned to your huzsband's or wife's needs.

The releasors of this film, a small company called Vanguard, offered us $50,000 to make a horror film. Sean said yo me, "Why don't you write it, direct it and cut it, and I'll produce it. We'll do it for $40,000 and pocket the $10,000. We'll do it in three weeks." So, I went out and wrote the script for LAST HOUSE ON THE LEFT, and the reaction to it was so strong, because it was just a crazy, wild script! Our agreement was that we would just hold nothing back. We would do the most outrageous things we could think of. So I wrote this crazy sort of ribald comedy, horror thing. And we couldn't get it out of the mimeograph place! That was the first sign that we had something special: they were all passing around the mimeographs to read!

We went out and we made the film. We went over-budget, and Vanguard had to give us another $40,000, so we ended up doing it for $90,000 after all. When it came out, it was immediately a big hit, and it's still playing. It was a sort of phenomenon, and I've been directing ever since -- or trying to direct. (laughter)

Q: Why was it also called KRUG & CO on some prints?

WC: It's an interesting story about how an advertising campaign and a title can influence a film. Originally, the working title of LAST HOUSE ON THE LEFT was THE NIGHT OF VENGEANCE. When it came out, we didn't like that, so we did a big contest among all the friends and relatives, and we came up with three titles: SEX CRIME OF THE CENTURY, which is part of the conversation Sadie and Krug have in the car at the beginning, when Sadie concludes that the greatest sex criminal of the century was Freud, because he made everybody self-conscious about sex. We also came up with KRUG & CO, because Krug was the main villain. Finally, LAST HOUSE ON THE LEFT was a title suggested by an ad man, whom we all though was terribly off the wall for suggesting such a title, which had nothing much to do with the film.

They opened it up in three towns simultaneously, all with the same demographic profiles, but using different ad campaigns. What an ad campaign determines is, who comes out those first, crucial two nights to get the word-of-mouth going. The first two nights in the towns with SEX CRIME and KRUG, nobody came. And in the town where they had the LAST HOUSE title, and the ad campaign that said, "Keep repeating, It's Only a Movie!", a crowd came out. And the next night, there was double the crowd, and it just took off. So it was a very dramatic example of how a title change and an ad campaign can work. To this day, there are people who still remember the ad campaign. You can hear the audience repeating, "It's Only a Movie!"

Q: Had you had any ideas for scripts before?

WC: As I said, they gave us money specifically to do a crazy horror film. Before that time, when I graduated from college with a Bachelor's in English, I was sort of undetermined between a musical career -- I was playing guitar in some of the cabarets in Chicago -- and I also had been writing short story and poetry. I received a full scholarship to John Hopkins' writing seminars under a poet named Coleman, so I decided to do that. So I studied writing and philosophy at Hopkins, and got my Master's Degree.

Then, when I got out, I didn't know what I could do for a living. So, after someone suggested I teach, I did just that. I was very fortunate. I put in an application at a place and there were no openings, so I started a job selling rare coins in Baltimore. But then, some English professor in Pennsylvania dropped dead of a heart attack the day before the classes started! I got this telephone call, and they said, "If you come out right away, you can have this job!" It's the story of my life! So I jumped in an airplane and ended up in Pennsylvania teaching college.

Q: Other than for the fact that it got you in films, do you feel that LAST HOUSE was a worthwhile experience?

WC: Absolutely! It's funny because I would never have thought of going out and doing a horror film, but now, I can see through whatever set of circumstances and luck that I was well-suited to doing that. The horror film is a typical way for a young film-maker to gain entree into the film-making world. It is a kind of film that can be made on a low budget, and that can make a great deal of money.

As I look back over my entire life, I can see that I always enjoyed spooky stories, and I always enjoyed doing outrageous things. So I was indeed suited to doing that kind of film, although it would have never occurred to me, at that time, to actually do a horror movie on my own. I was trying to write very artistic stories and poetry. I was going in totally different directions, and not getting very far, and all of a sudden, somebody gave me a chance to do something that I never would have allowed myself to think about doing. Because I was totally anonymous at the time -- I was living in New York on a shoestring -- I figured I would do this picture and nobody would ever know I did it, or even go see it! So I just went crazy and did this really bizarre movie. And then, everybody knew that I had done it, and I became notorious for doing that kind of movie. It's kind of ironic how it all happened!

Q: Did you have fun making LAST HOUSE?

WC: Yes, we had a LOT of fun making it! It was all friends that did it. Sean Cunningham and I were friends by that time, and we shot most of it in the homes of either his mother or his own backyard. We used friends of ours as actors, so it was a very homemade fun family movie, in a weird sort of way. Compared to some other shoots that I've had since, it was relatively trouble-free. I believe the original was shot in three weeks, then we went back for a fourth.

At the time, I didn't know about storyboards. I was sort of feeling my way as a director. So, I did weird things, like drawing lines in the script, like "this shot is sort of smilar to that shot on this page", and I would draw lines until it was such a mess I couldn't follow any of it! I really didn't know what the established procedures were for organizing a film. We had it budgeted, and we knew we had a certain amount for props and costumes, but beyond that, there was very little organization.

I didn't have much of an idea about what a director actually did, beyond shouting "Action!" and "Cut!". My orientation was more in documentaries, because that was the type of films I had worked on during that first year in New York. So I covered a lot of LAST HOUSE as a documentary film-maker would cover an event. The scene in the woods, for example, where the girls are first taken in the woods, I covered three times continuously, never stopping the action. Just played the entire scene as an event, and I had the camera stand in three separate places in general, and follow the action, and then planned to cut it together later. That scene had a real spontanous feel, so we would rehearse it before hand, and then just do it.

As a result, the editing of LAST HOUSE took nine months because it was such a mess. I didn't know what a master was. I didn't know how a master and reading a close-up could be used together. All of these things, I learned by either shooting a lot of material and then, finding out later that I should have done something else, or by finding from experience what worked and what didn't. But somehow, in the end, it all turned out O.K.

Q: Did you have to do a lot of trimming down on LAST HOUSE because of the violence?

WC: We had requests from sub-distributors, people in other sections of the country, who said that this film was too wild to play. They were getting audiences, but the audiences were tearing up the theaters! We had reports of people faiting, threats of lawsuits, fist fights and near-riots. We had a case of people trying to get in the projection booth and the projectionist had to barricade himself in! (laughter) Wait! We had a case of half an audience leaving and cowering in the lobby! (laughter)

We had lots of cases of projectionists and theater managers editing the prints themselves with scissors. We would get the prints back in pieces in the cans. So we voluntarily took out several scenes, two of which I don't really miss because they were so outrageously painful to watch, and one of which I think really hurt the film.

In the murder of Phyllis, the first of the girls to die, my whole intention was to show murder in a film that was as I would imagine it to be, rather than as it was depicted in films normally at that time. That is, the person delivered the killing blow, and the victim died, maybe with a few gasps, but not always. They would never fight a protracted fight, and would suffer clearly in front of the camera. So I did that with Phyllis, and I carried it through all the way, and the people that were killing her then went into a sort of psycho-sexual frenzy, where clearly they were going beyond what they even thought they were going to do, and it ended with them realizing that they had partially disemboweled her, and reaching down and pulling out a loop of her intestine. That was the point where a lot of people fainted...

But that, to me, was the REALITY of murder, because at that point, their whole character changed, and they were suddenly sober and horrified by what they had done, and we had to cut that out. To me, now, that murder, as it stands, loses the whole climactic rhythm of that sudden realization. I think it gave the film a truth that was very painful to watch, but also very real.

Q: Was there anything about LAST HOUSE that you didn't like?

WC: Oh, yes! The comedy scenes. I think the cliches of the stupid rural sheriff and his assistant did not work. All of us, for years, were under the influence of IN THE HEAT OF NIGHT and the stupid Southern Sheriff. Some of the sound is also terrible: the scene in the old Cadillac where Krug and the others are riding along and do the bit about the Sex Crime of the Century, was one of my favorite scenes in the script, but you can't hear it, because we didn't know how to mike people, and how to make any post-production dubbing either!

Q: Did you feel able, after LAST HOUSE, to go out and be a director?

WC: Yes, but the phone never rang! (laughter) It was quite a period of time. Because LAST HOUSE was so upsetting to the Establishment, I think I had only one call in two years, even though commercially the film was a big hit. That was from the producers of LET'S SCARE JESSICA TO DEATH, a horror film of about the same period. But Sean and I went out and wrote scripts for quite a while after that. We wrote comedies, we wrote a script on Vietnam, we tried to get serious, but nobody would take us seriously. So, I ended up accepting an offer from a friend of mine to do THE HILLS HAVE EYES. By the time, THE HILLS was out, people saw that there was not only this wildman, but somebody who knew how to sit and direct. From that, I got on a television show, and from there to some more wide acceptance.

Q: How did HILLS happen?

WC: Someone came to me and said, "Let's do another LAST HOUSE." He'd waited and watched me for years, and he knew that I wasn't having any success getting out of the genre. So he said to me, "So it might not be what you want to do, but you need some money to live on." At that time, I was virtually broke.

The idea of the specific story was my own. I researched quite a while in the New York Public Library on murder and mayhem in general, and ran across a story of a weird family which lived in Scotland in the 17th Century. They were cannibals living in a cave overlooking the ocean, and they would way-lay travelers between London and some other town. The whole countryside got the reputation of being haunted because those that went in didn't tend to come out. Finally, a husband and wife were attacked on their way home, and the wife was grabbed, but the man escaped and saw the people. He went back to London and brought back help. They discovered a cave with this in-bred family of about 25 people, and vats of human bodies pickled in sea-water. This wild and crazy family was captured and dragged back to London, and executed in a most bizarre and uncivilized way. That was my inspiration for the family in HILLS, which lived on the Nevada gun-range.

Q: Did you have a much bigger budget to shoot HILLS?

WC: Yes, but with inflation, it ended up being just about the same. We spent about $230,000 and we shot for five weeks. We still shot in 16mm, but we had special effects, like we blew up a big trailer, which was very exciting to us. We had animals; we did some stunts, which we had an actual stuntman do. We actually did some fun things!

Interview © 1999 Randy Lofficier