Vive le Silver Surfer!

(Originally published in Alter Ego Vol. 3 #1.)

A freakish, wandering celestial body threatens to collide with the planet Earth. Even the Silver Surfer is powerless to divert its course. But his numerous acts of charity and mercy raise the spiritual level of humanity as it waits for the Day of Judgment. This naturally upsets Mephisto, who dispatches his demons Belzebuth and Astaroth to spread new evil on Earth.

If you read every one of the eighteen original issues of The Silver Surfer when that Marvel comic was published between 1968 and 1970 and can't recall the above plotline--and if you don't recognize it from the hundred or so issues of the recent series, or even from the TV cartoon--

Don't worry, Frantic One! Seek not for a missing issue in your Silver Surfer collection.

For this adventure, entitled "La Porte Étroite" ("The Narrow Gate"), was published for the first and only time in two issues of a French comic book called Nova.

To understand how this came to be, we must now flash back to 1940s France.

I. From The Ashes of Defeat

The Nazis had taken over most of France in 1940. Even though the Axis powers and the United States were not yet at war, a side effect of the German occupation was the discontinuation of the import of popular American comic strips such as Flash Gordon, Brick Bradford, Prince Valiant, et al. French publishers scrambled to replace this material, and quickly turned to native French talent--and Italian imports, despite the fact that Mussolini's Italy was the ally of Hitler's Third Reich.

In the French city of Lyons, during the War, a young writer named Marcel Navarro was asked by the president of the publishing company S.A.G.E. to translate some Italian comics. While working for S.A.G.E., Navarro met writer-artists Pierre Mouchotte and Robert Bagage, both heavily influenced by American strips.

These three men were later almost singlehandedly responsible for a publishing explosion that produced a myriad of inexpensive monthly or bimonthly comic magazines, intended to satisfy the demand for harder-edged, more violent, more fantastic, American-style stories.

In 1946 Mouchotte started his own publishing company, but was ultimately driven out of business by a censorship law passed in July 1949 at the behest of Catholic educators and parents to monitor the contents of comic books. As a result of that law, most magazines were forced to go to a black-and-white, digest-size format and became known as the petits formats (small formats).

Meanwhile, Navarro had joined Éditions Sprint, for which he created the character of Secret Agent Z.302, drawn by Bagage under the pseudonym "Robba."

In 1946 Bagage left Sprint to create his own publishing company, the Éditions du Siècle (which would be renamed Imperia in 1952).

In 1947 Navarro, too, left Sprint, to go to Aventures & Voyages, another petits formats publisher, for which he created "Yak" and "Brik" for artist Jean Cezard.

Finally, in 1950, Navarro teamed up with would-be publisher Auguste Vistel to create Éditions Lug, which was also based in Lyons. (Lug was the ancient Gauls' god of commerce and trade, and the original Latin name of Lyons had been Lugdunum, "City of Lug.")

At first, Lug published the traditional mix of French and Italian series. But, unlike its competitors, Navarro (who used what he considered the American-sounding pseudonyms "Malcolm Naughton" and "J.K. Melwyn-Nash") actually created many of the characters, which were then entrusted to Italian studios to script and draw.

II. O Bitter Victory

In 1969 Claude Vistel, Auguste Vistel's daughter, who had just returned from a trip to the United States, convinced Navarro to publish the first translations of Marvel Comics in France, in a magazine entitled Fantask.

Unfortunately, Lug had repeated run-ins with the censors, who objected to the super-hero violence, the bright colors (deemed "garish"), and the various monsters, creatures, and assorted super-villains. The French censors had the power to decide that material was unsuitable for children, and force it to be labeled "for adults." In addition to keeping such magazines out of younger hands, the VAT (Value Added Tax) on adult material was twice that of material produced for children, making many marginal publications suddenly unprofitable. As a result of these factors, Fantask was cancelled after only six issues. In fact, it would seem the magazine was banned outright! (For a much fuller account of French comics censorship during this period, see articles in The Collected Jack Kirby Collector, Volume Two, published in 1998 by TwoMorrows.)

During these six issues, Fantask reprinted Fantastic Four #1, 3-10, 12, 14-18; Amazing Spider-Man #1-3; and The Silver Surfer #1-2, 4-6. The latter series in particular ("Le Surfer d'Argent" in French), was tremendously well-received.

Noted science-fiction author Jean-Pierre Andrevon, who wrote the book on which the recent animated film Light Years was based, favorably compared John Buscema's art to that of Burne Hogarth.

And the fascination of famed cartoonist Jean Giraud (Moebius) with the Surfer, which would eventually culminate in a legendary collaboration with Stan Lee twenty-odd years later, dates back to these groundbreaking issues of Fantask.

The undaunted Navarro re-launched the Marvel characters in Strange (1970 to present) and Marvel (1970-71), at first in a pocket-sized, duotone format, then switching back to magazine size and full color after a year or so. That was obviously careless, because it led to the cancellation of Marvel with issue #13, due again to problems with the censors.

The Surfer's adventures continued in Strange, which ran Silver Surfer #7-17--and #3, which had been omitted in the Fantask run, presumably in an effort not to upset the censors.

The last issue of the first Silver Surfer series, #18, drawn by Jack Kirby (which Stan Lee had done in order to find a new, more action-_oriented direction for the floundering Surfer comic), was thought to be too different in style and story from what had preceded it; it was not run in France until 1980 (in Nova #27, after "La Porte Étroite"), when the entire series was reprinted in the pocket-sized edition of Nova (1978 to date unknown).

III. A Star Is Born

Taking note of the public's interest in super-hero stories, Navarro had already begun to produce his own brand of characters, relying on the talents of various Italian artists as well as French writer Claude-Jacques Legrand and French artists Jean-Yves Mitton, Cyrus Tota, and Yves Chantereau. Notable Lug titles had published French super-hero-like material including the black-and-white Wampus (1969), which was released simultaneously with Fantask and was also discontinued after six issues because of censorship, Futura (1972-75), Waki (1974), Kabur (1976-76), Mustang (Series II, 1980-81), etc. (A future article in Alter Ego will explore in greater detail the various characters, especially the super-heroes, that appeared in these magazines.)

By 1979, as Nova was approaching the end of its rerun of Silver Surfer material, Navarro, frustrated by the lack of new material and emboldened by the character's ever-strong popularity, asked Marvel for permission to produce new Silver Surfer stories exclusively for the French market.

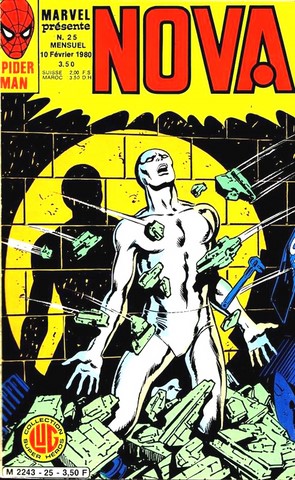

Permission was granted, and work began on "La Porte Étroite," which appeared in Nova #25 (22 pages; February 1980) and #26 (20 pages; March 1980). Credited to "J.K. Melwyn-Nash" (Navarro's pseudonym) and artist J.Y. Mitton, "with the permission of the Marvel Comics Group," this two-part, 42-page story ran alongside reprints of Marvel's short-lived hero Nova and of Peter Parker, the Spectacular Spider-Man.

Which brings us back to the first paragraph of this article, which is basically the plot of Nova #25, and thus bears a bit of expansion here:

IV. "The Narrow Gate"

The Silver Surfer detects a threat to Earth--the asteroid Ceres has mysteriously changed its orbit and is on a collision course with our world. Mankind doesn't realize it because humans lack the cosmic awareness of the Surfer. The only folks to find out (in a space shuttle) die when Ceres' gravity waves send their ship out of orbit.

The Surfer realizes that only Zenn-La's anti-matter-based "Weapon Supreme" (from S.S. #1) can destroy Ceres. He begs Galactus to let him go through the barrier which the space god created to keep the Surfer on Earth. Galactus refuses, but points out that when Ceres destroys our world, the Surfer will be freed; all he is to do is wait! Nevertheless, the Surfer vows to try to save his adopted planet.

The Surfer tries to alert the United Nations, but is scorned and hunted after he bursts into the General Assembly. He decides men can be reborn only if they die in a state of grace, so he decides to alleviate mankind's suffering until the catastrophe comes. He sweeps across the world, transmuting molecules into manna for starving masses, bringing rain to parched deserts, healing the sick in hospitals, all with his transmutational powers. (Clearly, Navarro had chosen to eschew super-hero violence to concentrate on the morality of the Surfer.)

All this goodness naturally arouses the enmity of Mephisto, who was looking forward to the arrival of four billion souls of sinners in his realm, thereby defeating the plan for Earth of his adversary (God). So Mephisto dispatches his demons Belzebuth and Astaroth (on spectral motorcycles!) to counterbalance the Surfer and to spread evil on Earth. Which they do, in spite of the Surfer's admonitions.

In a scene reminiscent of the "Temptation of Christ" sequence in Silver Surfer #3, Mephisto tries to bargain with the Surfer. He will free him, if the Surfer lets the humans die as they are. The Surfer naturally refuses. Then Mephisto offers a trade: the Surfer's soul against Earth's four billion. But the Surfer rejects that, too.

He returns to Earth to help fight the tsunami caused by Ceres' approach, but is instead blamed for it. Mankind still does not realize that it is doomed. The Surfer is struck down by lightning. (Mephisto's doing, or just dumb luck? The story never says.) Fallen, he is stoned and buried (except for his outstretched hand) beneath rubble by an uncomprehending mob. He appears to be dead. The doomed humans shamble off to await Doomsday--while the gleaming surfboard hovers above the debris.

In #26's "Deuxième Partie" (Second Part), the planetoid Ceres is getting ever closer to Earth. An almost unrecognizable President Jimmy Carter talks to a more recognizable Soviet premier Leonid Brezhnev. They decide not to tell their populaces the truth. Carter learns that the Surfer knew of Ceres' coming. The authorities go looking for him, but his body is gone.

For, meanwhile, a mysterious light (whose source is never revealed) shines down from the stars, takes the Surfer (board and all), revives him, and transports him past Galactus' barrier to Zenn-La. There the Surfer meets with Shalla-Bal, but he tells her they have no time to spend together. He must obtain the Weapon Supreme, which is kept in a space station in orbit.

With Shalla-Bal's help, he steals the Weapon and escapes in the ship that carries it. She is arrested for treason. The Surfer's ship escapes the Zenn-La fleet by going into hyperspace. He rematerializes it near the Earth and blasts Ceres out of the sky in the nick of time.

But the Surfer pays a price, of course. His ship is destroyed by the explosion, and he and his board topple down toward the Earth. He recovers, only to find that the uncomprehending New Yorkers (and presumably everyone else) blame him for the devastation caused by the space debris from the obliterated planetoid. The American and Soviet leaders plan to grab the credit and usher in a new era of world cooperation, and don't want the Surfer to interfere. The leader of the CIA comes up with the idea of blaming the Surfer and offering a reward for his capture.

Someone recognizes the Surfer (wearing a hat and trenchcoat) and tries to turn him in. The Surfer flees into the sky, but finds that he is again trapped within Galactus' barrier. He blames God for having given him a taste of freedom and then abandoning him. His final line of dialogue is a paraphrase of Christ's cry from the Cross: "Why have you forsaken me?"

The dialogue throughout this two-part adventure reads very much like Stan Lee's own prose (in translation, of course).

For his part, Mitton, a talented artist who has, since then, created numerous series of his own, was specifically instructed to copy John Buscema's style. Most of the figures were therefore taken directly from previous Silver Surfer stories, creating almost a collage effect. This, however, does not take away from Mitton's obvious strength and ability when dealing with contemporary city scenes and futuristic space action.

As a result, "La Porte Étroite" reads as an enjoyable pastiche of a Lee-Buscema story that might have been.

Artist J.Y. Mitton's Buscema-cloned cover for Nova #25. The Surfer's figure is a swipe from Silver Surfer #6 (June 1969), page 2, though with a bit more sheen. To see more of this rare Silver Surfer story, be sure to pick up ALTER EGO #1.

Silver Surfer ©1999 Marvel Characters, Inc.V. A World He Never Made

In spite of its qualities and promise, "La Porte Étroite" remained an isolated story, never to be followed by another. In an interview, publisher Claude Vistel revealed that Lug's deal with Marvel required it to pay the American company the same amount in royalties, whether the story was a translation from an existing Marvel comics, or a new story created in France by French talent.

This economic stipulation did not take into account the creative costs of generating new material, and made it financially impossible for Lug to continue producing new Silver Surfer stories. Lug allegedly pointed out that Marvel would own the resulting stories and presumably could have amortized the creative costs by publishing them in the United States, not to mention selling them to other countries than France, but to no avail.

The Silver Surfer had once again met the only adversary he could never defeat:

The Almighty Dollar.

© Jean-Marc Lofficier