Ivan Reitman on Ghostbusters

Ivan Reitman has had a unique, multi-faceted career, with achievements in motion picture and television production, direction, writing, etc...

A native Czech, whose family fled to Canada when he was four, Reitman's entertainment career was launched after winning a prize in a national student competition for the Canadian Bicentennial. As a student, Reitman had also directed and produced several plays that aired on Canadian television.

Reitman first met with actor Dan Aykroyd (Ray Stantz in Ghostbusters) when he produced a live television variety show, entitled Greed. Shortly thereafter, he produced Spellbound for the Toronto stage, which evolved into The Magic Show, a five-year hit on Broadway.

After The Magic Show, Reitman produced another Broadway show, based on The National Lampoon magazine. The success of this production enabled him to become acquainted with the famous magazine, and eventually led to the production of Animal House in 1978, starring John Belushi.

Reitman followed Animal House with Meatballs (1979) and Stripes (1981), both starring Bill Murray, who was going to play the character of Pete Venkman in Ghostbusters. Reitman directed Meatballs, co-written by Harold Ramis (Egon Spengler in Ghostbusters), who also co-starred in Stripes.

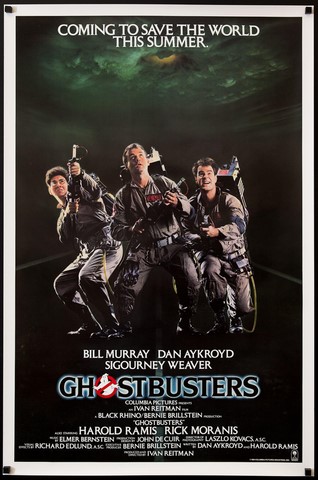

Then, in 1981, Reitman produced the animated SF fantasy picture, Heavy Metal, inspired by the magazine of the same name published by National Lampoon. In 1984, Reitman, Murray, Aykroyd and Ramis teamed up again to produce Ghostbusters, a zany SF epic which became the runaway hit of the year.

Randy LOFFICIER: When did you first get involved with Ghostbusters?

Ivan REITMAN: Dan Akroyd had written a script called Ghostbusters, and he showed it to Bill Murray. They liked it and they decided that I would be the director for the movie. They sent the script to me, and I didn't like it at all. I sort of hemmed and hawed about it, then I sat down with Danny and started discussing what I thought we should do with it. HE really liked the ideas. I also suggested that we get Harold Ramis involved as a writer and an actor in the film. That was last May. So, we started all over again, using his draft really for certain incidents and characterizations. We really redid it pretty well from scratch.

We worked all summer. Bill Murray came back from shooting The Razor's Edge in France, and we started shooting in October. It's not the fastest film I've ever been involved in, but considering the size of the film it's pretty remarkable.

RL: How much of the original script is still there?

IR: A lot of it is the kind of business that they're in. Two of the major incidents in the film were originally in that script, but reworked for the plot that we developed. His movie would have cost $200 million to make, it was more of a science fiction extravaganza than a comedy. I wanted to make a comedy that also had science fiction stuff and neat effects in it. But, I felt that the weight had to be on the characterizations and the comedy, rather than the other way around. Which was his script. I made it much more realistic, also in the process. I influenced its realism. They're the writers, and they did all the writing.

RL: Was there any resistance about changing it?

IR: No. Once Danny and I finally sat down face to face and talked about it, he was the most excited advocate. He couldn't wait and he seemed very appreciative of the whole development of it.

RL: After you got Harold Ramis in on the script, how long did it takae from the time you started changing things around till you had a completed script ready to go?

IR: That first draft took about a month or five weeks. We went off to Martha's Vineyard, stayed there two weeks and did another draft. Then, we did another draft after that, that took two or three weeks. We did three drafts in the space of two months.

RL: Were there significant changes from one to the next?

IR: It was clearer where the movie was going with each draft and what the character differentiation was amongst the three of them. What the major plot incidents should be. That kept on shifting around. The science line became clearer.

RL: While you were doing the script, were you thinking in terms of what the special effects would entail?

IR: Yeah. But we knew that we were going to be in real trouble, time wise. Right away, the studio was saying, "We need t his for next summer." and it was already less than a year away. Michael Gross contacted Richard Edlund, who we had heard was going to leave Industrial Light amd Magic, and set up a company here. I met him to find out what his plans were -- I think this was already in June of last year -- and he said it was true.

RL: Did you have any idea of what it would entail when you started out?

IR: I had a pretty good idea. I'd been through a little of this, so I had a pretty good sense of the scale to do it properly. It still cost more than we expected. But it seems to be coming pretty well for what's done.

RL: Shooting live action to be printed together with effects. No previous experience.

IR: Fortunately we had storyboards on everything, so I had a good sense of how it would be layed out. But we still don't know how everything is going to actually look, until it's done.

I think it was harder for the actors, because they didn't have anything specific to respond to. I always tried to give them as much visual information as I could, either from the storyboard or key development drawings that we had madae. And, to cover myself, I would do a number of takes that had a range of emotion, from more subtle to more broad.

RL: What other tricks did you use?

IR: I tried to assault the actors and extras as much as I could with wind and cork stuff and paper. I feel that as much as their physical environment can change, the greater the effect and the more realistic the response of the actors.

RL: What about the trials and tribulations of closing off Central Park for a week?

IR: They weren't happy about that at all. They felt that didn't have a good location manager. We should have been talked out of the location that we ended up choosing. It was right inthe middle of three very important arteries. Quite apart from the Central Park West, which is a north-south flowing... that was relatively easy to close. It was the east-west, crosstown traffic, flowing through 64th, 61st and 67th, right in the area where we were shooting. We had blocked those up too and one Friday night we apparently gridlocked Manhattan Island for about an hour.

RL: Didn't the Film Commission try to talk you out of shooting ther?

IR: Yes, they did. But by then it was too late, because we were deep into the building the big set that matched the exterior, and there was a lot of other moneey spent, specifically for that building.

RL: WHy did you decide to build such a massive set for the rooftop scene?

IR: John DeCuir, the production designer, is the last of the grand masters. It was appropriate to the story. For the confrontation, basically we needed.... I guess we could have built half of a rooftop, and sort of tried to play the action that way. But, it wasn't that great a savings, once you've built the scaffolding and everything, for the extra ten percent, you might as well go the rest of the way.

RL: What was shooting on such a big set like?

IR: Well, we couldn't shoot at any angle, but we had a fair amount of freedom. It was also so big, that it took forever to light. I think there are only 12 Titans existing in the world, and we used ten of them on the stage. During certain key scenes, no other filming could take place on the Burbank lot! So, we tried to do it during the Christmas break time, and we scheduled carefully those days, so it would occur when there was no other filming. I think the last time this kind of power was used was for the big set on Close Encounters, when the spaceship landed.

RL: What kind of pressures were you under, in trying to do this so quickly?

IR: THere was a lot of pressure. But, I'm a pretty quick study and having been so involved in the development of the screenplay, I had a pretty good idea of where I was going with it. I was lucky in that I had an extraordinary support staff.

RL: You're editing the film, yet the special effects aren't done. Is that a problem for you?

IR: Yeah! We have these sort of black and white slugs all over the place. They have just a plate or some crude line drawings in them. But one thing I learned from Heavy Metal, and from Space Hunter to a certain extent -- the film better work without the special effects or you can forget it. Whatever inadequacies we felt in the work picture of both Spacehunter and Heavy Metal didn't disappear when the film was completed. Even though we always told ourselves that, "Well, Spacehunter will work better once we actually see it in 3D, and it's all together with the effects." or for Heavy Metal, "Once all the color and effects are in it will work better." But, it didn't. It worked basically just the way it did, only it was more polished.

I screened Ghostbusters in its rough state, without any effects at all, except the mechanical ones that we did on set, to small audiences, just to see. I figured it was going to have to work as it is. It will only get better, but it better work right now. Fortunately it did. I found I'm no longer relying on the inclusion of everything to save me. My aproach now was, that its got to work as a movie without anything in its roughest form without special effects, audio effects, proper color balancing or music. If it works then, you know it's going to work. That's where we are now, I think. As I said at the beginning, my focus on this movie was that it work as a comedy about these three guys who go into business for themselves. That's what I think this story is about. These three very bright people who make a job change, and set up ths very unique business. It's the problems of setting up a business, keeping their relationship together and the problems they run into in this particular business.

RL: Where did the idea for the Stay Puft Man?

IR: I don't know where it came from, but that was one of the important things that we kept from the original draft.

RL: How did it strike you, when you read that your major antagonist was going to be a giant marshmallow?

IR: It was what worried me, because the film was very realistic until that point. As long as you accepted the theory as it developed, each thing led to the other quite naturally, and that's where it suddenly took a left turn and went way beyond. I kept on worrying that it might not work. And, going into filming I still thought that it might not work. Now that I've seen it, I think it works, but I won't be able to tell until I've seen it all complete.

RL: What did you have as a contingency plan in case it didn't work?

IR: The reason it stayed, was because we couldn't come up with anything that sounded as good, so we went with it. It's part of the risks of film making.

RL: Do you think that having to be a part of setting up a new special effects facility made your job more difficult?

IR: I think it made Richard Edlund's job more difficult. He had to build a company and get it up to working speed. They've only hit their stride about a month ago, so it put them into a terrible crunch, getting this film ready. For us, it's a problem, because it means we're rushed in terms of getting some of the effects done. There's 195 effects shots in the film at this moment. And, it was more expensive as a result of a lot of it going into the physical set up, as opposed to into the movie itself.

RL: What are you doing about scoring, since the film isn't yet finished?

IR: Elmer Bernstein started looking at footage in December, while we were still filming. We had reels cut together before we finished filming. HE's been working on it, and he's now into it very heavily. He's used to that kind of quick race.

RL: Other than giving yourself more time, are there things you would have done differently if you could have?

IR: No. This is the luckiest and happiest filmming experience I've ever been involved in. It just came together quickly and smoothly, and the filmming was generally a very happy experience. We weren't much over time and budget.

RL: Can you think of any funny incidents while you were filming?

IR: Well, I laughed everyday, that's how I remember it. I was laughing on the set, even when I was the most annoyed. I found many opportunities to laugh. That would be the best way to characterize what the filming was like.

Interview © 2003 Randy Lofficier