|

|

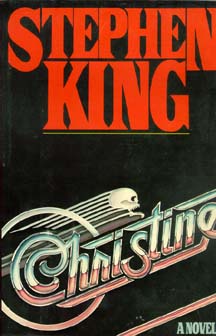

When Stephen King agreed to this interview [CONDUCTED IN 1984],

he had not yet seen the movie Christine,

and was therefore, understandably, not willing to comment on the film. He was, however, happy to talk about his

novel and his own feelings about the fifties.

LOFFICIER: It doesn't seem that Christine fits into your usual fictional "universe" of Maine or New England towns like Castle

Rock, 'Salem's Lot, etc...

Stephen KING: No, it doesn't,

although there is some reference made to the fact that Arnie Cunningham, on some of his fireworks runs for Will

Darnell, goes through the town of Stovington, Vermont, which is where Jack Torrance from The

Shining taught, and where the plague center was in The

Stand. The thing is that it takes place in Pittsburgh [Christine is dedicated

to famous Pittsburgh filmmaker George Romero, for whom King wrote Creepshow.], which is so far from the New England setting of the other stories. The books that I've

written have been located either in Maine or in Colorado for the most part.

Lofficier: There is a

picture of you with a Plymouth Fury on the book's dust jacket. Do you have a Christine?

King: No, that car actually

was loaned to us by a Pennsylvania outfit that handles vintage cars for movies. They ran the car over the New Jersey

line, just like in a Springsteen song. We did this photograph session almost like a rock-and-roll album cover.

The photographer, whose name was Andy Unangst liked the car so much that he bought it!

Lofficier: Why did you

pick a 1958 Fury as your subject?

King: Because they're

almost totally forgotten cars. They were the most mundane fifties car that I could remember. I didn't want a car

that already had a legend attached to it like the fifties Thunderbird, the Ford Galaxies etc... You know how these

things grow. Some of the Chevrolets, for example, were supposed to have been legendary door-suckers. On the other

hand, nobody ever talked about the Plymouth products, and I thought, "Well..." Besides, Lee Iacocca gave

me a million bucks!

Seriously, I don't know how Chrysler feels about Christine, anymore than I know how the Ford Company feels about Cujo, in which a woman is stranded in

a Pinto. But they should feel happy, because it's a pretty lively car and it lasts a long time. It's like a Timex

watch, it takes a licking and goes on ticking.

Lofficier: It's difficult

to tell from reading the book whether Christine is evil herself, or whether Le Bay makes her evil. From what source

do you see the evil emanating?

King: That's one of the

questions with which the movie people started to wrestle. Was it Le Bay, or was it the car? I understand that their

answer is that it was the car. In fact, it may be -- and I'm just guessing -- that Le Bay isn't anywhere near as

sinister as he is in the book. I think that, in the book, there is the suggestion that it's probably Le Bay, rather

than the car.

When the film people came to me, I said, "Look, this is your decision. You decide what you're going to do

with the story." But, later, I was told that in the opening sequence, when the car rolls off the assembly

line, one of the workman is dead behind the wheel. This would give you the idea that the car was bad from the beginning...

Lofficier: You seem to

bring up the fifties a lot in your work, and have a great deal of nostalgia about the times...

King: Sure. I grew up

in the fifties. That's my generation. I think there's been a fair amount of that from writers whom I would say

are now the "establishment." When I started writing, with Carrie, I was twenty-four, twenty-five, something like that. I was a kid. Since then, ten years have

gone by, and 1947 has become a very respectable birth year for writers.

So, there are a lot of us who actually developed our understanding of life, and who grew to be, not adults, but

thinking human beings in the fifties. I've got a lot of good memories from the fifties. Somebody once said that,

"Life was the rise of consciousness." For me, rock-and-roll was the rise of consciousness. It was like

a big sun bursting over my life. That's when I really started to live, and that was brought on by the music of

the fifties.

Lofficier: Do you have

any more macabre memories of the fifties?

King: No, I don't. All

the macabre things that I can remember, and that come out of reality, rather than from something that I made up,

started with the Kennedy assasination in 1963. I don't have any bad memories of the fifties. Everything was asleep.

There was stuff going on, there was uneasiness about the bomb, but, on the whole, I'd have to say that people in

the fifties were pretty loose.

Lofficier: Do the horror

aspects of your writing come from having read E.C. comics and that type of thing?

King: Oh, God knows! Some

of it has to, sure, because those comics really grossed me out when I was a kid, and they also fired my imagination.

They were two different ways in which those things have become really important to me in what I do. The gross-out

business isn't nearly as important to me as just sort of flipping people out, so that they say, "Jeez! This

car's running by itself!"

Christine is an outrageous kind of riff

on one cord. I mean, this car's out there running by itself and getting younger! It's actually going back in time.

An audience can relate to a certain degree to something like a haunted house, The

Amityville Horror, traditional horrors like ghosts, vampires and things like

that.

You give them a car, or any inanimate object, and you're suggesting something that is either along the pulpy lines

of the E.C. comics, or else obviously symbolic. The car is a symbol for the technological age, or for the end of

innocence, when it plays such a part in adolescence and growing up. When you do that, you're really starting to

take a risk. But, that's also where the excitement is. If you can make somebody go along with that concept, that's

really wonderful.

Lofficier: Do you consciously

try to put something a little more subliminal into your work?

King: No, never subliminal.

I think it should be out there where anybody can see it. I don't believe in the idea that symbolism, or theme should

be coded so that only college graduates can read it. The only thing that that type of self-conscious literature

is good for is for people to dissect it and use it to get graduate degrees or write doctoral thesis. Theme and

symbol are a very strong and valid part of literature, and there's no reason not to put them right out front.

Lofficier: Why was Christine written using two different narrative styles,

Denny's first person narrative for the opening and closing parts, and third person narrative for the middle?

King: Because I got in

a box. That's really the only reason. It almost killed the book. It sat on a shelf for a long time while I walked

around in sort of a daze and said, "You know, this is really cute. How did you do this!" It was like

when you paint a room, and you really do end up in a corner saying, "Aw, heck! Look what I did! There's no

door at this end of the room!"

I had Dennis telling the story, and he was supposed to tell the whole story. But then he got in a football accident,

and was in the hospital while things were going on that he couldn't see. Then, for a long time, I tried to narrate

that second part in terms of what he was hearing, hearsay evidence, almost like depositions. But that didn't work.

I tried to do it a number of different ways, and finally I said, "Let's cut through it. The only way to do

this, is to do it in the third person." I tried to leave enough clues, so that when the reader comes out of

it he'll feel that it's almost like Dennis pulling a Truman Capote. It's almost like a non-fiction novel.

I think that it's still a first-person narration, and if you read that second part over, you'll see it. It's just

masked, like reportage.

Lofficier: Do you plan

on doing a Christine II, with the car

coming back across country?

King: God, I don't want

to go back through that again! Once was enough! All I can think of would be if the parts are recycled, you'd end

up with this sort of homicidal Cuisinart, or something like that! That would be kind of nice!

Interview © 2001 Randy Lofficier

|